In Cold War Berlin, an Affair Born of Chaos and Control

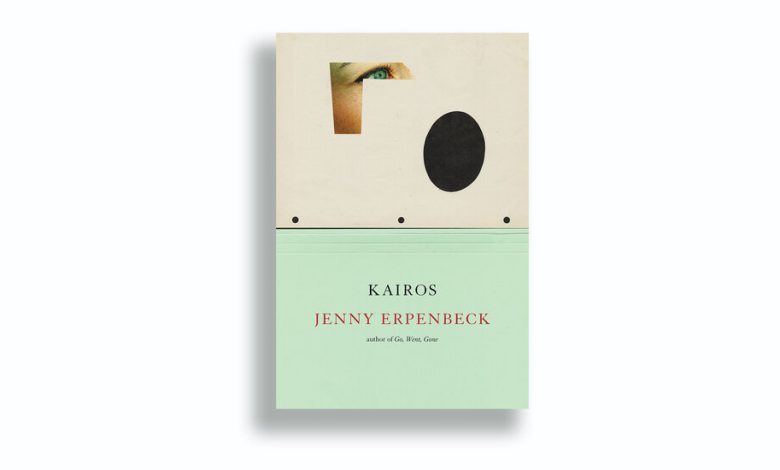

KAIROS, by Jenny Erpenbeck. Translated from the German by Michael Hofmann.

The first thing to know about Jenny Erpenbeck’s new novel, “Kairos,” is that it’s a wallow. I was in the mood for one. It’s a cathartic leak of a novel, a beautiful bummer, and the floodgates open early.

Iris Murdoch described the shedding of tears as “usually an action with a purpose, a contribution even to a conversation.” Samuel Beckett took a dimmer view. He wondered if tears were “liquefied brain.”

In “Kairos,” which is about a torrid, yearslong relationship between a young woman and a much older married man, the tears are of every sort: smart and stupid, ugly and otherwise, precipitated by pleasure, pain, laughter, confusion.

This is East Berlin in the late 1980s, just before the fall of the wall. The young woman, Katharina, is a theater design student. Her eyes are described as “fishy”; at the start, she is 19.

Hans, a 50-something novelist and high-minded writer for radio, is handsome and rangy, and he looks fine with a cigarette. Katharina doesn’t like to weep in front of him, so when she anguishes one evening over a coming internship that will keep her in Frankfurt for a year, she waits until he steps out to run some errands:

To witness someone else’s tears is not necessarily to be moved yourself. But to absorb “Kairos” is — like reading “Wuthering Heights” or “On Chesil Beach,” listening to albums like Lou Reed’s “Berlin” or Tracey Thorn’s “A Distant Shore,” watching the film “Truly, Madly, Deeply” or ingesting an ideal edible — to set yourself on a gentle downward trajectory.

If “Kairos” were only a tear-jerker, there might not be much more to say about it. But Erpenbeck, a German writer born in 1967 whose work has come sharply to the attention of English-language readers over the past decade, is among the most sophisticated and powerful novelists we have.

Clinging to the undercarriage of her sentences, like fugitives, are intimations of Germany’s politics, history and cultural memory. It’s no surprise that she is already bruited as a future Nobelist. Her work has attracted star translators, first Susan Bernofsky and now the poet and critic Michael Hofmann.

“Kairos” is Erpenbeck’s sixth book of fiction to be issued in English. Her previous novel, “Go, Went, Gone,” was published in the United States in 2017. It’s about a retired classics professor who becomes embroiled in the fate of African refugees in Germany. I found it powerful but often tendentious.

“Kairos” — the title refers to the Greek god of opportunity — is her earthiest novel to date. It’s not just the sex; this is a novel in which pansies are said to resemble Karl Marx and looking inside a stranger’s refrigerator is said to be as good as going to the cinema. She is also writing more closely to her own unconscious.

Yet the sex is devastating, and not because it’s especially explicit. Early on, Hans and Katherina’s lovemaking (“his hands discover that her bottom fits neatly into them, a peach to each”) is scored to Mozart’s “Requiem,” a black disk on his turntable, and the music expands in each of their minds without the moment verging, even for a moment, on the ridiculous.

“Do all the assembled horns, bassoons, clarinets, timpani, trombones, violins, violas, cellos, and organ serve her will?” Erpenbeck asks. They do. This writer is preoccupied with how culture starves humans and how it fills them up, and even more so with what we take from it and what we leave behind.

Hans is old enough to have been, as a boy, in the Hitler Jugend. Katherina, whose life overlaps with Erpenbeck’s to a certain degree (both worked in publishing before moving into theater work) is “one of those children who have been through every phase that the Socialist state prepared for them — from the blue neckerchief to training in production and Russian classes, to harvest help in Werder — to make them citizens of the future.”

The future that arrives is not the one either expected. When the novel begins, Katharina has never been to the West. Hans suggests to her that freedom tastes a bit like a salade niçoise after all the frankfurters and potatoes back home.

Their sex grows more intense, and more violent. We have been here many times before with the young woman and the older man who wishes to part her from her family, friends and underpants. But Erpenbeck plays it, for the most part, straight.

Their affair is conducted on a psychological plane. It swamps them both. They share a hypnotic, Milan Kundera-like absorption in its permutations. He beats her; she mostly enjoys her submission. She feels her life has met its moment.

Through these scenes the novel’s themes play out: chaos and control, freedom and its opposites. He is a serial philanderer. When she cheats on him once, in a minor way, he exacts such sustained revenge that it’s like watching a horror movie: The reader mentally pleads for her to flee. It’s as if he is sending her to the bottom of the sea.

His surveillance, his total control, take on political ramifications that I won’t spoil here. I don’t generally read the books I review twice, but this one I did. “Kairos” left me with an itch I needed to scratch, after the absolved and the condemned begin to flow west though the Brandenburg Gate, after all certainties are shattered. About German history, we read, “Whose job is it to go down into the underworld and tell the dead that they died for nothing?”

The book has an intricate frame — thematic planks that didn’t fully emerge, for this reader, the first time through. Erpenbeck writes: “A strange trick of paper to become a document. Strange trick of paper to produce deceptions.”

This profound and moving book has a subterranean force, and it made me recall lines from the Polish poet Adam Zagajewski’s posthumous collection, “True Life,” published earlier this year:

KAIROS | By Jenny Erpenbeck | Translated from the German by Michael Hofmann | 294 pp. | New Directions | $25.95