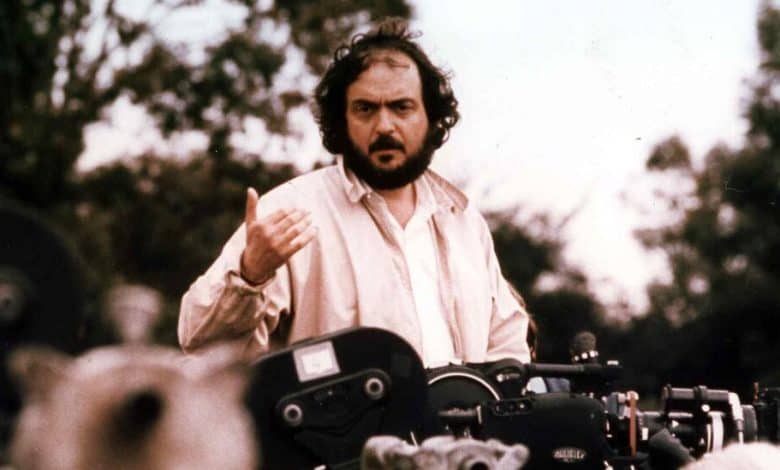

A New Biography Tackles the Remarkable Career of Stanley Kubrick

KUBRICK: An Odyssey, by Robert P. Kolker and Nathan Abrams

The passions, obsessions, habits, talents and fears that shaped the extraordinary movies of Stanley Kubrick were well chewed over in his lifetime. Some of the reporting came from those who knew him; other impressions came from journalists who didn’t know him, but enjoyed the digging. It was easy quarrying, because there was so much rich topsoil. A son of the Bronx who became the self-styled squire of Childwickbury Manor in Hertfordshire, England, Kubrick was a visionary filmmaker whose greatest works — including “Paths of Glory” and “Dr. Strangelove,” “Lolita” and “2001: A Space Odyssey,” “The Shining” and “A Clockwork Orange” — are as vital and prescient about culture and society today as they were when they blazed through the second half of the 20th century.

But for Kubrick to be Kubrick took so much fussing on his part, and scurrying on the part of others! He had his routines, his rituals, his ways of working. He immersed himself in slow-simmering, yearslong research to decide on whatever his next project was going to be; he insisted on many many many many takes for each camera shot, with a commitment to “perfection” — the usual term used — that regularly drained those around him, including actors and crew, family and friends, artistic collaborators and insurance claims adjusters. (He filed work-related insurance claims as regularly as other people floss. Surprisingly, there is no record of how diligently Kubrick flossed.)

A short list of the man’s insatiable interests included sex, the Holocaust, chess, Freud, Napoleon, the treacheries of marriage and the works of the Austrian writer Arthur Schnitzler. Schnitzler’s 1926 novella “Traumnovelle” — “Dream Story” — simmered within Kubrick for decades until it became “Eyes Wide Shut,” his last film. The simmering shows, in a movie as impermeable and deracinated as it is weirdly mesmerizing, not least because the galactic movie star Tom Cruise and his then-wife, Nicole Kidman, went all in for Kubrick’s fevered ride.

With a slender 13 features in his filmography, Kubrick operated at a painstaking crawl. After an absence of a dozen years, he was completing “Eyes Wide Shut” when he died of a heart attack in 1999, at the age of 70. (The son of a doctor, he distrusted doctors.) And then the real chewing over of Stanley Kubrick’s work and life began.

Frederic Raphael, who collaborated with Kubrick on the screenplay for “Eyes Wide Shut,” jumped in quickly with a memoir. Michael Herr, who worked with Kubrick on the screenplay for “Full Metal Jacket,” wrote a memoir. Kubrick’s personal driver wrote a memoir. “The Stanley Kubrick Archives,” published in 2008, dazzled with its handsome presentation of so much of the man’s project-related stuff. The film scholar Robert P. Kolker analyzed the work of Kubrick in an expanded edition of “A Cinema of Loneliness” in 2011. Nathan Abrams, a professor of film studies with a special interest in the intersection of Jewishness and cinema, published “Stanley Kubrick: New York Jewish Intellectual” in 2018. Kolker and Abrams together produced “Eyes Wide Shut: Stanley Kubrick and the Making of His Final Film” in 2019.

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in.

Want all of The Times? Subscribe.