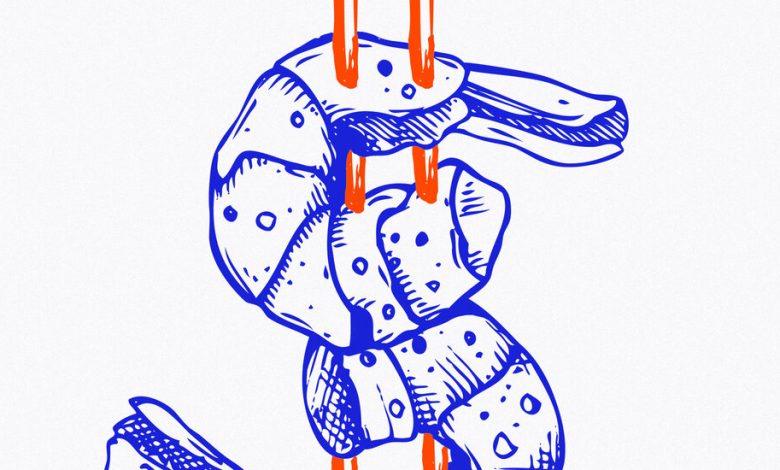

Want to Better Understand America? Consider All-You-Can-Eat Shrimp.

The great economist George Stigler wrote a paper called “The Cost of Subsistence” that calculated the minimum cost of food that would satisfy the nutritional requirements of “an active economist” who “lives in a large city.”

He calculated the nutritional value of 77 foods, including yummy ones like chocolate, strawberry preserves, bananas and leg of lamb, but concluded that they were all too expensive. In his article for a 1945 issue of The Journal of Farm Economics, he settled on just five foods based on their August 1939 prices, in these quantities per year: 370 pounds of wheat flour, 57 cans of evaporated milk, 111 pounds of cabbage, 23 pounds of spinach and 285 pounds of dried navy beans.

Stigler hastened to say that this was purely an academic exercise, not a diet recommendation. “It would be the height of absurdity to practice extreme economy at the dinner table in order to have an excess of housing or recreation or leisure,” he wrote.

Still, I thought of the Stigler diet this week when the news came out that Red Lobster, the seafood restaurant chain, had cracked under pressure and filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. One source of its problems — not the biggest, but the easiest for customers to grasp — was an every-day-all-you-can-eat shrimp promotion last year that got too popular and was a key reason for an $11 million quarterly operating loss.

The connection, of course, is that Red Lobster’s offer was taken advantage of by diners who thought like Stigler. Once they paid $20 for the special (later bumped to $22 and then $25), the marginal cost of every shrimp they popped into their mouths was zero. That probably attracted some economizing types who weren’t even regular customers of Red Lobster.

I’m going to speculate a bit here. I wonder if changes in the economy and society have made people more prone to exploiting all-you-can-eat deals to the max. Trust in big business is the lowest on record, according to Gallup polling. So diners may feel less compunction about taking advantage of a big business’s marketing slip-up. At the same time, people are feeling economically stressed, so “free” is even more enticing than usual.