When We See the Climate More Clearly, What Will We Do?

This month MethaneSAT, an $88 million, 770-pound surveillance satellite conceived by the Environmental Defense Fund and designed at Harvard to precisely track the human sources of methane being released so promiscuously into the atmosphere, was launched by SpaceX, to great fanfare.

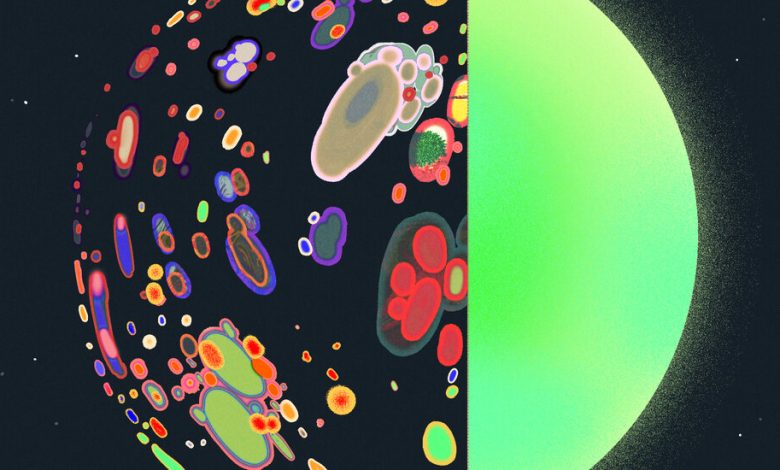

Methane, a somewhat less notorious greenhouse gas than carbon dioxide, is produced by industrial and natural processes — leaking oil and gas infrastructure, decomposing melted permafrost, the belching of cows and the microbial activity of wetlands. We’ve known that methane is producing a lot of warming and that there is a lot more of it in the atmosphere now, but we didn’t have the full picture. Beginning next year, MethaneSAT will begin beaming down everything picked up by its spectrometer, providing a publicly available quick-turnaround methane-monitoring system that has filled the hearts of climate advocates and data nerds with anticipation. What will it see?

The hope is that it will see a map of climate malfeasance that doubles as a global to-do list. MethaneSAT is not the first effort to track emissions from space, but its launch has been accompanied by a wave of can-do climate optimism for four big reasons.

The first is that methane really matters. By some accounts, it explains about one-third of warming since the Industrial Revolution, with estimates steadily growing in recent years, along with the astonishing rise of its concentration in the atmosphere. The second is that actually doing something about the emissions from fossil-fuel infrastructure shouldn’t be that hard or that expensive. Human activities are responsible for about 60 percent of all methane emissions, and according to the International Energy Agency, 40 percent of industrial emissions are avoidable at no net cost, with the balance of the industrial problem solvable for the price of just 5 percent of last year’s fossil-fuel profits. The third is that those benefits would arrive quickly. Methane, unlike carbon dioxide, dissipates quickly, whereas you have to wait for centuries or even millenniums to get the full temperature benefit of zeroing out carbon dioxide, so we can clear the atmosphere of human-produced methane in about a decade. And the fourth is that all of the pretty granular MethaneSAT data will be publicly available, scrollable and shame-able for anyone who cares to scan its website for burps or flares of planet-heating gas from at least 80 percent of the world’s fossil-fuel facilities.

This probably sounds like progress, which it is, on balance. But the satellite will probably bring some bad news, too. One of the scientists who developed it described the launch as “like looking over the edge of the cliff,” and almost invariably, whenever we get a better look at methane emissions, the problem appears bigger than we’d thought. The latest example is a revelatory paper, published in Nature last week, which surveyed U.S. oil and gas infrastructure and found that the country’s fossil-fuel industry is producing three times as much methane as previously estimated by the E.P.A.

The figure is both shocking and predictable. Previous Environmental Defense Fund research suggested that annual methane emissions from oil and gas were 60 percent higher than the E.P.A. had estimated. Last year, work published in The Proceedings of the National Academy of the Sciences suggested it was 70 percent higher. Globally, the International Energy Agency estimates, only about 5 percent of methane emissions were reported to the United Nations by the companies responsible. Reporting by countries was a bit better but still covered less than half of the total estimated by the agency. The Guardian documented more than a thousand superemitter events around the world in 2022. Leaks from just two fossil-fuel fields in Turkmenistan that year warmed the planet more than all the carbon emissions produced that year by Britain.