Can a Designer Be Successful and Subversive? Rick Owens Walks the Line.

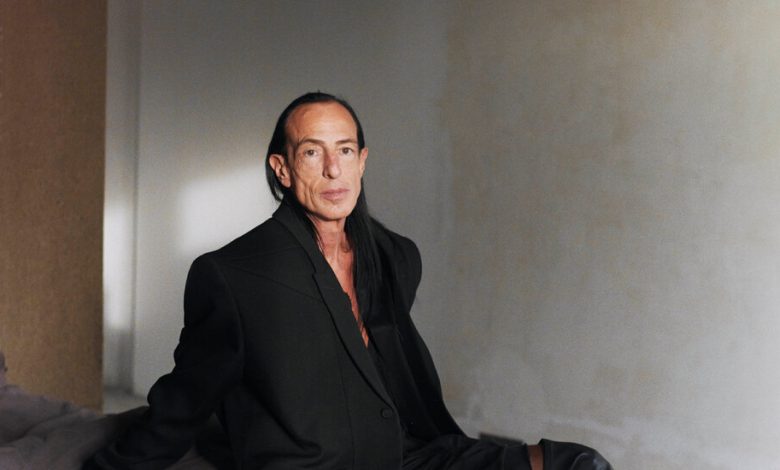

ON A DREARY November day in Paris, the soft morning light is creeping into the American fashion designer Rick Owens’s 18th-century mansion, just south of the Seine in the Seventh Arrondissement, where he and his French wife and business partner, Michèle Lamy, 80, have lived for 20 years. One of the few truly independent creative heads of a major brand, he’s built an improbable empire by making clothes as grotesque as they are glamorous. But three decades into his career — and a few days after turning 62 — Owens finds himself at a crossroads. He’s just returned from a birthday trip to the Pacific Coast of Jalisco, Mexico, where he rode horses with his muse, design assistant and frequent travel companion, the towering 30-something Australian model Tyrone Dylan Susman, whose Instagram feed has also shown them among Greek ruins, in the Dubai desert and on beaches around the world (where they’ve been known to wear matching baseball hats with each other’s names on them). Now that Owens is back, he and Lamy, a 5-foot-2 agent of creative chaos with kohl-rimmed electric blue eyes, gold-plated teeth and two young grandchildren, have been overseeing their latest project: relocating the Rick Owens men’s and women’s runway shows, normally staged in the monumental courtyard at the Palais de Tokyo, a neo-Classical-style structure housing two museums with stone colonnades and a large reflecting pool, to their living room.

transcript

My Favorite Artwork | Rick Owens

The fashion designer discusses an earthwork by the land artist Michael Heizer and his helicopter trip to see it in person.

Hi, I’m Rick Owens. [MUSIC PLAYING] Probably, my all-time favorite is Michael Heizer’s “Double Negative,” because he took the status of art outside of the gallery, and he placed it so far away that there’s almost an arrogance that you have to go find it. I tried to go there one time, but we got lost in the desert because the road to get to it is so impossible. So we had to rent a helicopter to fly over it. That was the closest I ever got to “Double Negative.” I sense a lot of testosterone and ego. There was something a little bit more sincere about it to me, something about becoming one with your environment in such a primal, primitive, huge, grand, explosive way. I feel that every time I go swimming in a sea or an ocean, I feel like I’m having intercourse with the world, which makes me feel insignificant in the best way. I identify with the sense of expressive bombast. But I feel that what I’m doing is a very gentle proposal to reconsider good taste or the standards of conventional beauty, which can be very, very rigid.

The fashion designer discusses an earthwork by the land artist Michael Heizer and his helicopter trip to see it in person.CreditCredit…Gautier Billotte

“I think it’s become too bombastic,” he says of the Palais de Tokyo shows as he scans the gutted first floor of what was once the French Socialist Party headquarters. (When he and Lamy arrived in 2004, the five-story townhouse had been sitting empty for two decades; today, its chalky walls and floors — not part of an ongoing renovation but the finished product — conjure a squat more than a residence.) “Subliminally, I think I’ve been designing collections to match [the Palais’s] grandeur.” His extravagant productions, often presented against a sky of colorful smoke bombs or amid flame-engulfed pyres for hundreds of “freaks,” “weirdos” and “messy queens,” as he affectionately refers to his loyal followers, have incorporated step dancers (spring 2014), exposed penises (fall 2015) and women harnessed to each other (spring 2016). The new location, though smaller, isn’t without its own sense of spectacle: Near where the former French president François Mitterrand’s desk used to be is a big stack of felt made from human hair by the Serbian artist Zoran Todorovic; two black plywood chairs with antlers from the Rick Owens furniture line; and, atop a plinth in a plexiglass case, a 1.3-gallon aluminum tank containing the sperm of the Estonian rapper Tommy Cash. “It’s empty now,” says Lamy, in an off-the-shoulder black Rick Owens dress that matches her ink-dipped fingers. “We’re waiting for him to drop some more off.”

Owens is wearing a black skullcap, black slouchy cotton shorts and black leather sneakers with thick white rubber soles, all designed by him. The platform heels he often wears make him seem much taller than 5-foot-10. When the couple’s French architect, David Leclerc, tells him it’s likely not possible to switch out a white enamel radiator for a stainless-steel alternative, Owens agrees to settle for something equally “delicious.” (He uses the same word to describe the nightly footfalls of the guards — “Daddy,” he calls them — patrolling the Ministry of Defense next door.) Leclerc frowns: It’ll be difficult enough to install the mirrored walls and indoor rock garden in time for men’s fashion week in January. (Their exchange recalls the 1966 “Addams Family” episode in which Morticia Addams, having insisted on decorating her neighbors’ home, talks about adorning the walls in salmon. “Pink?” they ask hopefully. “No,” Morticia replies. “Scales.”) But construction sites merely make Owens nostalgic for his early days in Paris, when he and Lamy worked out of “a filthy barn kind of thing” with a single Turkish toilet in the Bastille area. “Everything was covered in concrete dust. Remember, Hun?” he asks Lamy. (He calls her that, not unfondly, because, like the Huns, he says, “she’s a marauding, ax-wielding primitive force of nature who takes what she wants and then throws a lit match behind her.”) “It was looking so good,” she replies with a grin.

Despite their many similarities, Owens and Lamy are also very different. The English fashion designer Gareth Pugh, Owens’s former protégé, says, “Michèle has this nomadic hustling mentality. Rick’s very happy to keep his head down and do the work.” Owens appreciates conventional beauty, if only for the thrill of perverting it; Lamy rejects it altogether. His dressing room is appointed with mimosa-scented candles, fresh-cut hortensias and throw pillows; hers has a pile of wet towels on the floor. Their other two residences — a minimalist apartment in Concordia sulla Secchia, Italy, near the factory where Owens’s clothes are made, and an equally austere beach house on Venice’s Lido — are too bourgeois for Lamy. “She’s like, ‘I don’t understand who these are for. Who are you?’” says Owens. “She’s offended that they refute our story together.”